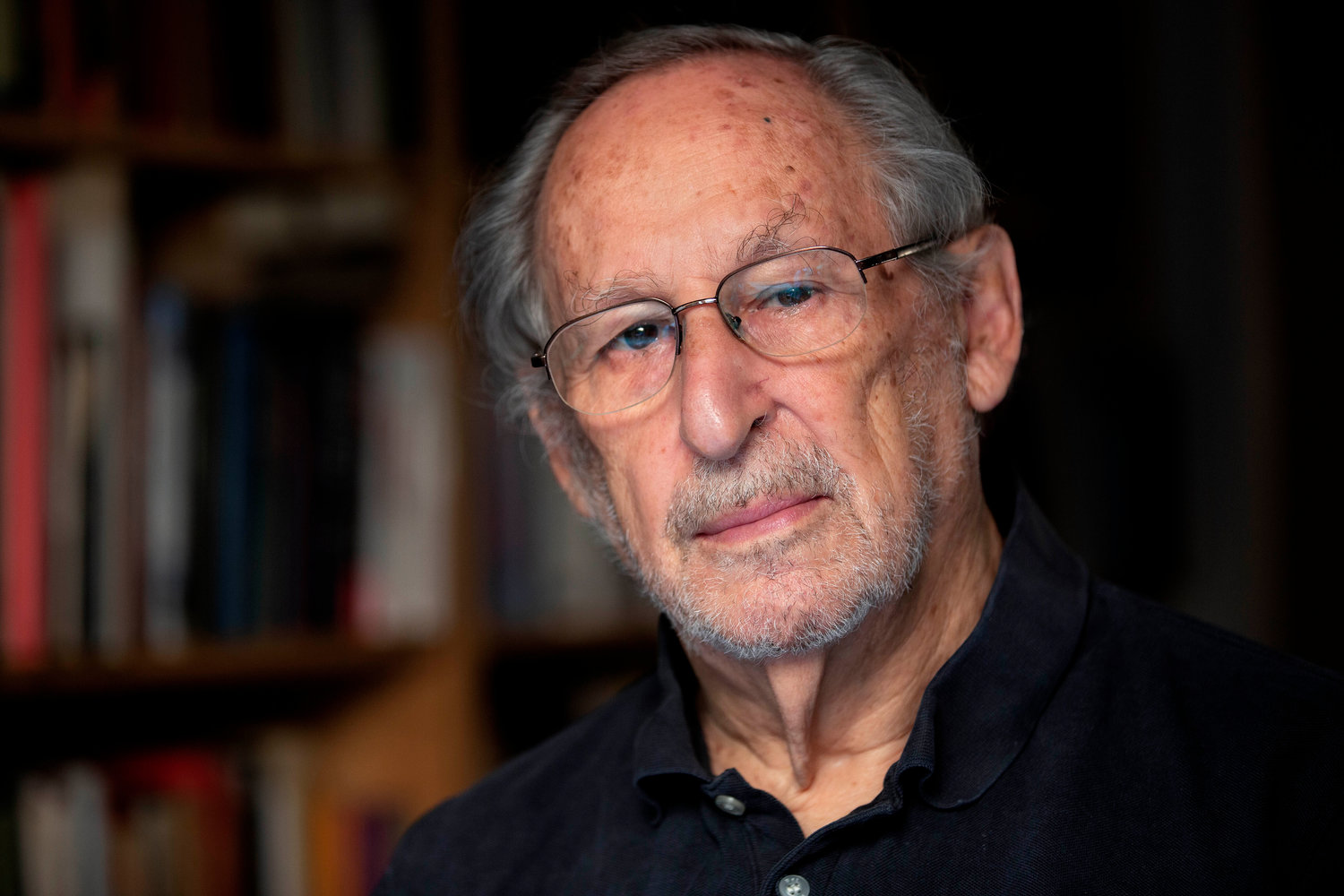

In an interview with the Associated Press published on June 24, Benjamin Pogrund stated that Israeli annexation would turn Israel into an apartheid state. “There will be Israeli overlords in an occupied area. And the people over whom they will be ruling will not have basic rights,” Pogrund described the potential future of Israel.

Prolific denier

Benjamin Pogrund was born and raised in South Africa and witnessed its Apartheid-era atrocities firsthand. He became a renowned writer on the topic and fostered friendships with Nelson Mandela and Robert Sobukwe as he wrote on Black issues in the white-ruled South African state.

But while Pogrund strongly opposed Apartheid in South Africa until its fall in the 1990s, in 1997 he moved to Israel and became a prominent denier of the similarities between the two countries’ treatment of their native populations. Not counting those people living in the occupied territories as citizens, Pogrund denied their treatment as apartheid-like.

Like many Israel apologetics, he made the convenient distinction of not counting Israel’s atrocities and racism outside its walls and fences. He authored a 2007 New York Times op-ed highlighting several successful Arab Israeli citizens as evidence for an absence of racial discrimination, while ignoring the people in occupied territories under de-facto Israeli rule.

Cognitive dissonance

Pogrund would, in the same article, deny that Jews and Arabs receive different treatment while also arguing Palestinian refugees could not return because they would become a majority, destroying Israel’s “purpose” of being a Jewish state. Those who called for a boycott on Israel Pogrund would label as antisemitic, while interpreting Israeli acts as a “response to Palestinian terrorism.”

For decades Pogrund has ignored the obvious similarities between both apartheid regimes. He appears to have conveniently ignored that while South Africa was in its last stages of shaking off colonization, Israel is still actively colonizing native land.

He downplayed the wall seperating Israelis from the West Bank as “mainly a wire fence, except in populated areas” that was there “primarily to keep out would-be suicide bombers.” By Pogrund’s definition, if South African whites had chased away the country’s Black population and kept them in occupied areas as does Israel, there would not have been “apartheid.”

After decades of witnessing and opposing South African Apartheid, he has spent the rest of his career making pro-Israeli arguments, similar to those of the South African regime that justified violence against Black citizens, as a logical government response to “violent terrorists.”

Changing definitions

Pogrund opposes annexation because it would undermine the cognitive dissonance that he and many others have applied to the Palestinian people living in the occupied territories. Annexing their land would result in them being considered to be some sort of Israeli citizen, and suddenly their treatment would indeed “count” as apartheid.

“At least it has been a military occupation. Now we are going to put other people under our control and not give them citizenship. That is apartheid. That is an exact mirror of what apartheid was,” Pogrund said.

Pogrund started to have doubts when, in 2018, the Israeli parliament enacted the “Nation State Law.” This defined Israel as the nation state of the Jewish people while downgrading the status of another ethnic group, Arab Israelis. Yet, he frames his opposition not as revulsion with the treatment of local Arabs, but instead fears that it would reduce safety and prosperity for local Jewish Israelis.

Annexation

The increasingly colonial attitude of the Netanyahu government appears to have posed something of an intellectual crisis for Pogrund as he has slowly learned of his own complicity in defending Israeli actions. News about the government’s annexation plans made him unable to write on the topic: “I couldn’t bring myself to do it,” Pogrund said, adding that “quite frankly, I just feel so bleak about it, that it is so stupid and ill-advised and arrogant.”

Pogrund has long been a critic of Israeli treatment of the Palestinians, describing the occupation of the West Bank as “tyrannical,” but has avoided using the word apartheid. He considers the term “a deadly word” that requires “intentionality” and “institutionalization.” That intentionality and institutionalization already exist in the occupied territories, and by annexing these areas, even deniers like Pogrund will no longer be able to refute the obvious.

“Come July 1, if we annex the Jordan Valley and the settlement areas, we are apartheid. Full stop. There’s no question about it,” Pogrund said.