Much has been said about the global drug trade. Movies about drug kingpins from the 1980s and 1990s are made into popular TV series like Netflix’s Narcos or into blockbuster movies like Scarface. But the real story of modern-day drug traffickers is much more complex.

Recent UN reports have allowed us a deep insight into the practical experience of being a drug trafficker in Afghanistan. Presented in a narrative, every step of the journey is based on specific facts from the stories told by people who traffic opiates across Afghanistan to this day.

Growing up in Afghanistan

The Afghani name for a drug trafficker is Quchaqbar, a word you will have undoubtedly heard if you were born in Afghanistan. Growing up in a province like Kandahar, on the border with Pakistan, will have meant that whether you like it or not, the drug trade will most likely be a big part of your life.

Let’s say you are in your late teens, you’ve lived in Kandahar all your life and your dream is to be a doctor when you grow up. There is a university in Kandahar where you could study, but first, you will have to manage to get out of your village with enough money to support your education.

Unfortunately, there is very little work where you live. Asking around at local farms and shops quickly reveals a harsh truth, without a job, how would you ever be able to realize your dream, or even feed yourself? When you discuss your predicament with your cousin, he mentions that he knows someone who could help you; his uncle might have a job for you.

You had seen his uncle drive around town in his 1994 Mercedes-Benz before, and wondered how he could have become rich enough to afford a nice car like that. When you meet him he asks you if you have a working smartphone and whether you know the area, after which he explains the job: You are about to become a Quchaqbar.

The first steps

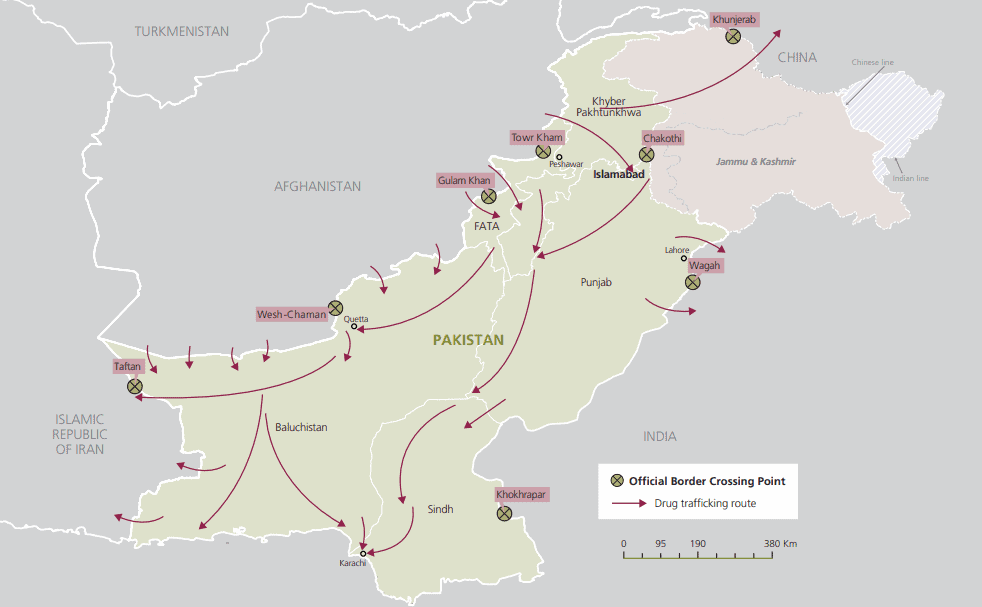

You are told to deliver something to Spin-Boldak, a town on the Pakistani border. But first you are told to find a route to get there safely. Using your knowledge of the area, combined with digital maps on your phone, you scout a route through the mountains where you are unlikely to meet anyone. You discuss the route with your new employer who gives you advice on how to avoid risks and what you can do to not get caught. After every detail has been carefully discussed you are told to wait two days, when bad weather will help you avoid detection on your journey.

When the day finally arrives you visit a small laboratory outside of town. You recognize one of the men working there, he used to be a chemist in the town’s pharmacy before it had closed a few years ago. Two girls, roughly of the same age as you, hand you two different packs, each with their own strange stamp on it. “If you have to get rid of one, pick this one” the girls tell you. The least valuable pack contains Morphine, while the other has a much more valuable product: Heroin.

With the two packages stuffed in your backpack, you set off towards the mountains.

On the road

As you hike across the mountain you are glad that your employer gave you so much information. You were told to avoid certain areas, as Taliban forces there would demand a bribe of up to 10% of the value of your cargo. He has done a background-check on the person you are to meet in Spin-Boldak, and taught you ways to hide the packages if you come across the Afghani border patrol. If you do need to pass a government checkpoint, you have been taught to bribe a local woman or child to carry the packages on them as you cross.

As you make your way to the border you pass villages and areas controlled by other trafficking organizations, often local families working together to supplement their meager income.

You are glad that these local groups often cooperate with each other and do not regularly fight like the Mexican and Colombian cartels you have seen in movies. The cover provided by the weather and your well-planned route mean you make your way to the busy border town without running into the black humvees of the Afghan Border Patrol.

Delivery

In the town of Spin-Boldak, near the border with Pakistan, you find the person you were to meet. The man has a strange accent, he tells you he grew up in Australia and his dual-nationality will help him get the packages across international borders. Your employer had made sure this person could be trusted long before you set off, and after you hand him the two packages he tells you to go to a ‘hawalar,’ a link in the informal Hawala money-transfer network.

After a quick phone call to your employer, you receive a password to give to the man. When you do, a big pack of bills comes out and after the Hawalar takes his cut, you have made more money than your father could make in a year. As you set off to return to your village you realize you are one step closer to saving up for university. But will you ever get a regular job now that you know how much money can be made?

What it all means

Variations of this story develop every day in Afghanistan. Young Afghanis traffic morphine and heroin from province to province, until they reach the border. Young women often enter the trade if their husband or the family’s breadwinner passes away. For them there is work in growing opium, working in labs, or acting as couriers.

Poverty and lack of legal employment means there are few options for young Afghanis who want to study or simply provide for their families. Because the trade is so pervasive, finding someone who can offer you a ‘job’ in the industry is often very easy. And once someone has entered the business, it is hard to get out as legal jobs make only a fraction of what Quchaqbars can make.

As long as there are no other options, everyday another young person in Afghanistan will start their journey to become a Quchaqbar, whether they want to or not.